Never before has our vision of the future of Emergency Departments (EDs) been as challenged as it is today. Emergency caregivers are inventive, adaptable and rise to any challenge. We want to share with you some of the ideas, strategies, and tactics that we have developed or that our clients and contacts have shared with us from around the world in their response the COVID19 virus.

With COVID19 impacting nearly every hospital in the world, and specifically the Emergency Department, each organization and group of healthcare leaders, clinicians, facilities engineers, architects and engineers have done their best to rapidly position their EDs for successful response to the virus. This article summarizes concepts that have been implemented “on the run” in the midst of the pandemic as well as defining future flow, technologies, and design issues to consider in the future to better prepare the worlds EDs for the next pandemic or epidemic event. With the insights we have gained through designing hundreds of EDs around the world, we will draw on our personal experience as well as the gathered insights of healthcare professionals around the world.

Written by:

Jon Huddy, AIA, NCARB, MArch, BA

David K. White, MBA

Malcolm Creighton, MD FACEP

Duncan Sissons BSc, Dip Proj Man (RICS), MRICS, MAPM, FIHEEM, MIoD

Special thanks to key contributors including:

- Brad Borden, MD FACEP

Cleveland Clinic, Ohio, USA - Debra West, MD

Assuta Ashdod Medical Center, Ashdod, Israel - Gunnhildur Peiser, Project Manager

University Hospital, Reykjavik, Iceland - Eric Sherman, PE, LEED AP, CxA, HFDP

Specialized Engineering Solutions, Nebraska, USA - Sean Keogh, MD, Service Line Director

Caboolture Hospital, Queensland, Australia

Pandemic Impacts on the ED

The impact to EDs have been staggering for both the US and England. While initial volumes overwhelmed many EDs worldwide, ED volumes now tend to be sharply down for two primary reasons:

- People are staying away from the ED for less urgent conditions because they are afraid of coming in contact with potential COVID19 patients and or healthcare workers

- There are fewer trauma patients as people have dramatically reduced driving and other outdoor activities. While many states continue their “stay at home” policies, the UK has seen the “over 70s” age group non-COVID symptom patients have practically disappeared from EDs altogether. Further definition of the age group utilization of England’s EDs can be found at https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/urgent-emergency-care/urgent-and-emergency-care- mythbusters

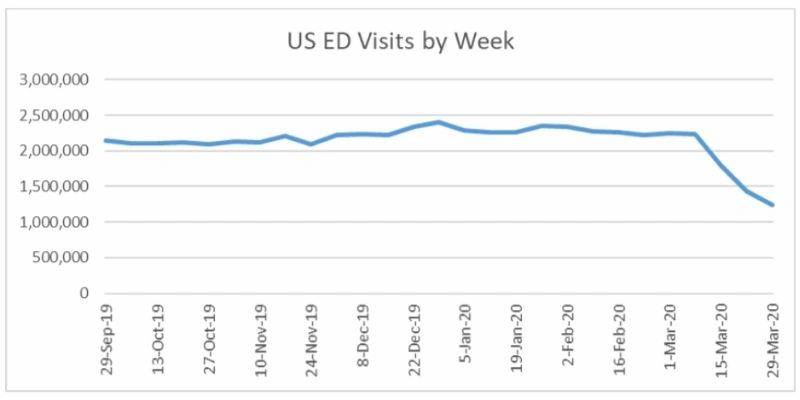

In the US between September 29, 2019 through March 7, 2020 total weekly visits to the ED averaged 2,250,329 patients. The week of March 15, 2020 weekly visits dropped by 20% to 1,794,020. The most recent data (week of March 29, 2020) had a weekly ED visit drop of 45%, down to 1,245,869. (source: CDC National Syndromic Surveillance Program (NSSP): Emergency Department Visits Percentage of Visits for COVID19-Like Illness or

Influenza-like Illness September 29, 2019 – April 4, 2020 Data as of April 9, 2020). See chart below for the actual ED weekly volume data in the US:

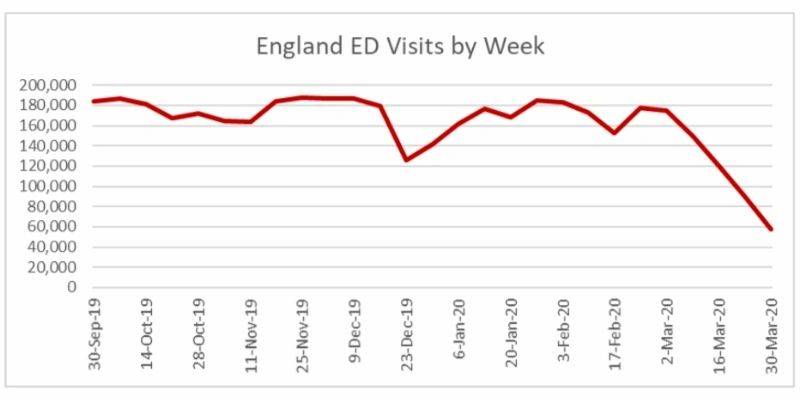

The same trends were being reported in England. The chart below shows the weekly Emergency Department volumes as reported by Public Health England via the weekly Syndromic Surveillance System: England bulletins. This includes only to attendances at Type 1 EDs.

In England, between the week of September 30, 2019 and March 1, 2020 EDs total weekly ED visits averaged 174,428. By the week of March 23, 2020 weekly volumes had decreased over 30% from that average and by the week of March 30, 2020 there was a 67% drop from that average in weekly ED volumes.

However, although volumes are down The Royal College of Emergency Medicine also reported that in March 31.5% of patients required admission to the hospital in England, the highest ever admission rate for ED patients. The US has been experiencing the same trend with higher acuities and higher admission rates as the lower acuity patients are staying away from the ED.

Immediate vs. Long-Range Considerations

We will start this article with simple comments on flow and use of existing physical space that can be considered for immediate implementation. We also understand that some of the items are pretty obvious and have most likely been considered by many healthcare professionals and implemented in many facilities, but we didn’t want to “gloss over” any item no matter how simple. We will continue the article by focusing long-range planning or more “intrusive” changes to your site, facility, and engineering infrastructure for both the mid-range timeframe (in coming months) and long-range design considerations for the future. Many of the items covered in this article have already been implemented in recent designs for new/future or recently refurbished EDs and thus have positioned many EDs for a more rapid and successful response to the COVID19 virus.

Redefining Patient Access and Flow

One of the first considerations for positioning the ED for a successful processing of patients is defining the access points, screening areas, and pathways for

“potentially infected” vs. regular/injured/other patient types. The quantity and type of “entry” and “exit” points for an ED has always been a struggle of “flow” versus “security” in that multiple entrances and exits may accommodate more comfortable flow of the patient while raising anxieties for security personnel having to monitor the additional entrance and exiting doors.

Pre-pandemic we see many EDs in the US, and almost all EDs in the UK, utilize the old-fashioned flow of “Walk in – Reception – Sign In – Return to Public Area – Call to Triage – Return to Wait – Called in for Treatment when Exam Room Ready.” Obviously, the biggest risk in this flow is the public waiting area with human to human airborne transmission as well as the impacts of transmission from hard surfaces. In the US and UK, new flows are being developed with many ED in the UK using a redefined flow (that still includes walking in the same entry door) which includes:

“Walk in – Specific Covid 19 Triage Process – Patient Streamed to

Symptomatic (Isolation Stream) or Non-Symptomatic areas”

However, many new EDs being designed in the US today are considering the same flow of outpatient surgery facilities that create the opportunity for arriving patients to avoid the path of existing or exiting patients. While, admitted, this flow concept was more for the emotional comfort of arriving patients to assist in lowering their anxieties, this flow pattern has assisted in the response to the COVID19 event.

Similar to the grocery stores that are now defining “one-way” circulation into their stores, through their aisles, and out of their stores to limit interaction of customers, the same is true for the ED patients. The EDs that have separate “in” pathways and “out” pathways and doors are now best positioned to limit the mixing of arriving and exiting patients. Existing EDs should consider how they may accommodate a similar flow in their existing environments.

A potential “alternate” exit may be use of your decontamination shower. While the virus is having devastating impacts on many EDs, the decontamination shower still remains underutilized overall and not really utilized in any form of virus testing or treatment. Clients are considering the decontamination shower (that has an exterior access door and an interior door into the ED) as a potential discharge “corridor.” The challenge may be that the decontamination shower may be at the back of the ED and away from public parking. Newer EDs actually have the decon shower closer to the public area since our experience shows that most patients needing decontamination at the ED usually are ambulatory/walk-in patients (covered in petrol, pesticides, fertilizer, etc.) since most ambulance patients are decontaminated at the scene of contamination prior to transport. In the UK, the decon shower many not be available as a secondary exit since some EDs do not have facility-integrated decontamination showers and instead utilize storage areas near the ED that house inflatable “decon tents” where persons can disrobe and be showered before entering the building sometimes via a side door.

We know of hospitals that have taken this “separate patient flow” systems to the extreme by utilizing existing hospital space outside of the actual ED for processing of COVID19-symptomatic patients. They have reorganized underutilized clinics and office space, which may be temporarily closed to other patients/people, and are utilizing these satellite areas as virus-testing and holding spaces. The intent is get any virus-symptomatic patients out of the ED as rapidly as possible, test the patients, then admit them to bed wards or discharge them out of the hospital through another area of the facility thus avoiding the incoming ED patients all together. However, the challenges are many to converting and utilizing non-clinical space (such as offices) for clinical functions as noted by Eric Sherman, a senior healthcare engineering design specialist working in the state of Nebraska which is in the middle of the United States.

“Activating other areas of the facility to test patients or reconfiguring them as surge space or makeshift ED’s allows the benefit of compartmentalization of patients type and the ability to treat inside the facility; but, it spreads out staff and many of these spaces are not equipped with ED-level engineering infrastructure for power, medical gas, and air changes. To overcome these challenges and support the temporary spaces, engineers have teamed with facilities personnel to implement a number of modifications. Temporary heating and cooling, shifting air handling units into 100% outside air, creating compartments of negative airflow, adding HEPA units, adding exhaust fans, upgrading and cross-connecting medical gas infrastructure, and adding temporary plumbing stations are just a few of the provisions incorporated the modify facilities to deal with the current crisis of COVID19.” –

– Eric Sherman, PE, LEED AP, CxA, HFDPa

Specialized Engineering Solutions, Nebraska, USA

Obviously, this extreme change in flow has larger impacts to staffing, the ventilation of various areas of the hospital, ability to convert spaces to isolation/negative airflow through portable HEPA filter systems, and the overall concern of flow and impact to other patients throughout the hospital. Circulation paths and distance to unit are major considerations if other areas of the hospital will be considered for extended ED assessment and testing zones.

Re-Use of Medical/Surgical Beds

The biggest concern for hospitals with the COVID19 virus has been lack of availability of ICU beds and ventilators for the patients that require those, particularly in the US, where the potential need for ICU beds far outweighs the need for Med/Surg beds. The University of Washington IHME dataset forecast a projected peak shortage of over 9,000 ICU beds by mid-April in the US, but was also showing a surplus of over 1,200 Med/Surg beds at the same time. This also incorporates historical bed utilization which has been drastically reduced with the cancellation of all elective procedures. (source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). COVID19 Hospital Needs and Death Projections. University of Washington 2020). While early projections for England showed that demand would exceed capacity for both ICU beds and Med/Surg beds, more recent estimates in England showed 40,000 spare beds in the system excluding the Nightingale beds. UK wards have been repurposed with hospitals significantly increasing their ICU beds stock. The problem now is shortage of equipment and suitable trained staff. ICU staff-to-patient ratios traditionally are 1:1 but many Trusts in the UK are now accepting 1:3. The UK also is taking advantage of the reduction in elective surgery activity and many sites are using operating theatres as ICU space.

In the US, with staff being shifted from Med/Surg inpatient bed units to assist care givers in the ICU’s, we are seeing continuing delays in getting Med/Surg beds assigned for ED admitted patients because existing units are being closed for this staffing shift to ICU. Our co-author Dr. Malcolm Creighton from Lahey Hospital and Medical Center just north of Boston recently experienced extended waits for ED admitted patients needing traditional Med/Surg beds since they were available but not staffed due to the workload transition to the ICU floors.

Multiple Entry Points

Our clients that chose to create separate adult and pediatric entrances into the ED now have the ability to re-designate these entrances as “potential infectious” and “other” patients. These multiple entrances mean that a “clinical decision point” needs to be created outside of the ED where a clinical professional is making the decision for flow and access point. The portable structures and tents that have been implemented at most ED sites are allowing clinical professionals to screen the patients and define their clinical flow for entry into the ED. Clients that don’t have multiple entrances are reviewing other “fire exit doors” that allow ED personnel to exit the ED in case of fire or security event, and reconsidering these “exit points” as new entry points for defined patient types. Re-use of the entry/exit points need to be planned carefully with security staff to determine how these doors will be accessed and controlled without exposing the ED to various security breaches.

Reception Desks

For the past few years there has been a tug-of-war between the people that believe EDs should be “soothing, welcoming spaces” with open reception desks versus the people with elevated security concerns who espouse physical separation and glass (or bullet-resistant glass) between the public and the “greeting” personnel. Obviously, the days of “completely open” reception desks will be gone and a level of separation with transparent panels will be integrated to limit the human-to-human transmission of future viruses via respiratory droplets. Similar to the plexiglass panels at most store check-out desks, a new level of “separation” will be considered for all ED greeting/reception spaces.

Ambulance Access, Donning and Doffing Considerations

Many of our ED clients have defined areas for doffing and cleaning whether it is for personnel or for ambulance backboards, stretchers, etc. While most ED’s have

areas that mix dirty and clean backboards in areas just outside or inside the ambulance vestibule, more care and consideration is being given to the “flow” of dirty/decon/clean processing and storage of ambulance crew equipment. The flow of arriving ambulance patients also needs to be considered regarding injured/other patients and the virus-symptomatic patients. Many of our clients are “arriving” non-symptomatic patients to the walk-in entry point defined for non-symptomatic walk-in arrivals. Now that many patients are being assumed carriers but non-symptomatic, even this flow is being challenged due to all patients being treated as carriers with the suitable protocols being observed.

Overall, whether it is ambulatory/walk-in or ambulance arrivals, the avoidance of intake area patients and the flow of discharged and admitted patients should be an

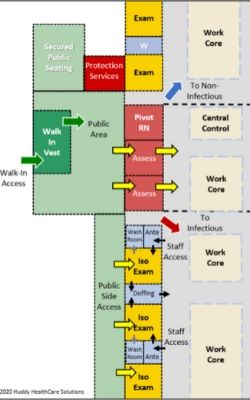

Access to Isolation Rooms and Zones

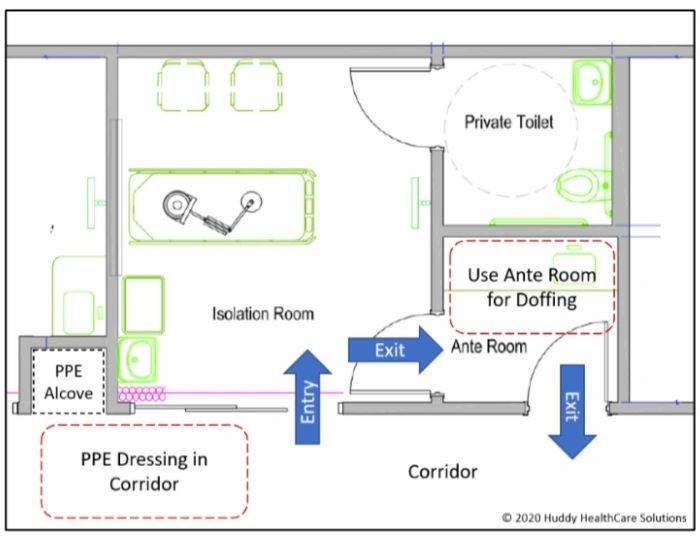

Historical ED design shows that architects and clinicians usually placed the air-isolation negative pressure rooms at the back of the ED, usually near the decontamination shower that was next to the ambulance entrance. While this is still a preferred location for some of the isolation rooms, new designs also include isolation rooms at the front of the ED adjacent to, or in, the triage area. Newer EDs should have access to isolation rooms right from the public walk-in area (see diagram to right) allowing patients to be taken directly into an isolation room without traveling through the central part of the ED.

An immediate solution may be to take an exam room(s) near triage, that are on an outside wall with windows and position a portable HEPA filter with discharge air out of the window to create a negative pressure room near patient intake. These rooms most likely will not meet isolation room requirements with ante-rooms, private toilets and exact air pressures, but they may allow for securing a patient in the short term in a negative air environment.

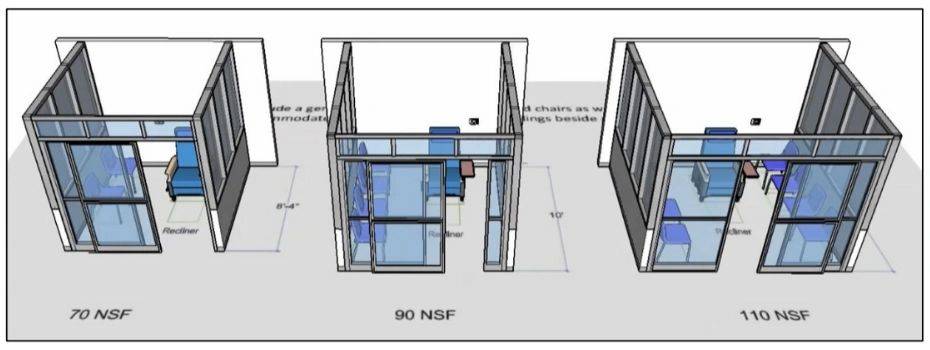

Internal Results Pending

Internal waiting rooms and results pending areas are being incorporated in most EDs around the world with the intent of getting patients out of the public area as quickly as possible. These areas support testing to be implemented as quickly as possible and allowing for a location to await results. Now that rapid COVID19 testing is becoming more accessible, the need to have a staging area for these patients awaiting results needs to be created so single patients aren’t taking up exam space during this waiting period. Historical Results Pending Rooms were nothing more than just an internal waiting room with multiple chairs for patients and family members. With “social distancing” which is being recommended by nearly all healthcare experts, the use of these rooms is being reconsidered. A certain level of separation now needs to be implemented in any results pending area.

A few samples of this separation can be found in in the diagrams to the right. Full height separation panels (lower diagram right) is the preferred configuration as EDs continue to develop results pending areas. Some ED clients are going further and considering enclosed cubicle seating areas seen in the diagram below. While limiting the number of family members in the ED, these cubicles allow family groups to remain together while awaiting tests and are preferred by children’s Emergency Departments because of the multiple siblings that may accompany a parent and sick child. There are multiple temporary and modular construction solutions that would allow these results pending cubicles to be immediately implemented in the ED.

Isolation Care Zones

Most existing EDs have already worked to split their ED into “COVID” and “Non-COVID” zones. And, while most of these “splits” are just physical separation without complete “air pressure” separations, the planning for different “air pressure zones” is now coming to the forefront. Nearly every ED we work with considers the zoning of mechanical systems and then decides against it due to the cost of creating separate mechanical zones. This has been a learning experience for most clinical professionals.

“Our ED is relatively new and has been operational since 2017. As a clinician, I thought splitting our existing ED into air-isolated sections would be easy. During design phases I never worried about what was occurring above the ceiling or behind the walls. In hindsight, I should have had my clinical team understand the benefits and limitations of the engineering infrastructure plan and how it could impact segmenting of our ED in the future.”

Malcolm Creighton, M.D. FACEP

Chief of Emergency Medicine

Lahey Hospital and Medical Center

Burlington, Massachusetts, USA

Hot – Warm – Cold Zones

While almost all EDs have split themselves into COVID-symptomatic and non-symptomatic zones, Chair of the Emergency Services Institute and Vice Chief of Staff at Cleveland Clinic, Brad Borden, MD, FACEP, who oversees over twenty EDs in the US and Abu Dhabi, believes that zones should be considered for three areas – “hot, warm and cold.” This segmentation would allow “very definite” COVID cases to be split away (in the “hot” zone) and separated from the “warm” zone for patients with selected COVID19 symptoms (such as respiratory complaints but no fever) and a third zone for the remaining patients with non-COVID related chief complaints. Dr. Borden adds “this type of patient zoning means that the pod system design feature, as well as maximizing bed quantities, should be major considerations in future ED designs.

Multiple Decontamination Zones

Larger EDs, such as the 200,000-visit, 164-bed ED we designed at WellStar Kennestone Hospital north of Atlanta, Georgia, have created multiple decontamination zones. By creating a decon zone near the walk-in entrance and another decon zone for ambulances on the other side of the building, allows for multiple access points for both walk-in patients (main entry vestibule and walk-in decon shower entrance) and ambulance arrivals (ambulance vestibule and ambulance decon shower entrance.) These multiple entrances allow COVID19-symptomatic patients and non-symptomatic patients to be split into different entry points no matter what arrival point they utilize. However, it should be emphasized that these multiple entrances only be utilized as staff-determined access points, and not utilized as patient self-directed entrances with complicated and confusing signage (… since we all know that the more signage you put in place the less people read the signs!)

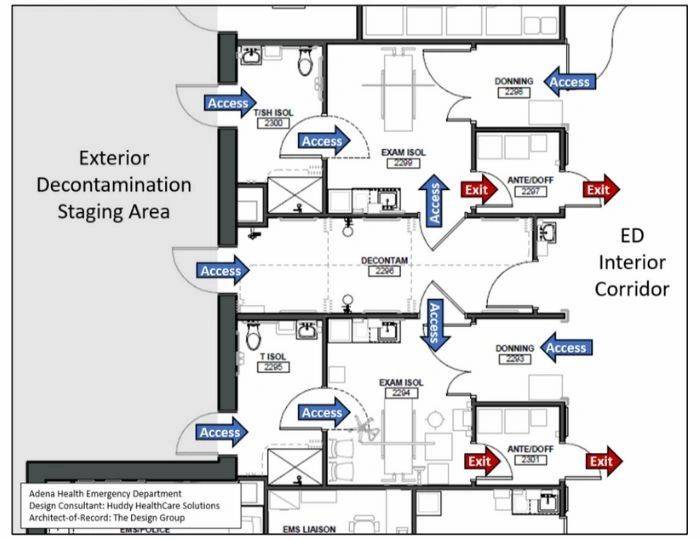

The WellStar Kennestone ED includes a complete “isolation care zone” that is immediately accessible from the ambulance decon area. This isolation zone can be segmented from the ED and includes multiple isolation rooms within the zone that include separate ante-rooms and doffing rooms. On the front side of the ED, the walk-in decontamination facilities includes immediate access to multiple isolation rooms inside another care zone that can be segmented from the remaining ED.

In England, where private ED treatment rooms are limited compared to the availability of curtain cubicles, the COVID-symptomatic patients are placed in care zones that may have air-locks and negative pressure. However, with limited private rooms or isolation rooms, the open areas mean that patients are not isolated from each other. This is leading to patients that may have symptoms, but not the actual virus, may be contracting the virus in the open environments. Any patient wrongly diagnosed and placed into this environment cannot be subsequently moved to the non-symptomatic area. The lack of widespread testing in the UK means that should any of these patients subsequently develop COVID symptoms, every patient in this ED zone may need to be considered infected.

Multi-Floor EDs

While very limited in the UK at this point, more and more EDs in the US are being designed on multiple floors due to limited space within hospitals or limited space on hospital sites. A sample is the WellStar Kennestone ED that is located across the street from the main hospital and has two levels of ED care space with additional floors servicing the roof-top heliport and bridge back to the main hospital. While splitting an ED on multiple floors brings operational and staffing challenges, this split of care space now allows the consideration for separate COVID units on different levels further separating patients. In addition, with the reduction in overall ED visits being experienced in most US EDs, a large ED such as WellStar Kennestone can consider utilizing the upper floor care zone to accommodate admitted COVID patients thus expanding the hospital’s inpatient staging capacity. However, alternate care or staging areas needed to be weighed against potential virus spread as Dr. Malcolm Creighton reminds us that “motion equals spread.”

Our client at the University Hospital (Landspitali Vossvogur) Emergency Department in Reykjavik, Iceland, utilized multiple exterior trailers and both floors of their ED:

“We utilized quarantine mobile trailers positioned by the ambulance bay. Pivot Nurses screened for signs of COVID in the first trailer and, if suspected, patients were directed to the other isolation trailers for testing and results waiting. By the time the pandemic peaked in the last few weeks, a recently emptied admin building next to the ED was adaptad to be a COVID assessment clinic open until 8 pm. In our ED, we utilized two sections on two floors of our ED that there were cut off with air lock doors as areas for COVID patients. With our usual 70,000 visit-ED down by 40% we could accommodate 4 COVID rooms on our lower floor and 6 more on our upper floor giving us locations to treat both higher and lower acuity COVID patients in separate locations.”

Gunnhildur Peiser, Project Manager

University Hospital and Emergency Room

Landspitali – Fossvogur, Reykjavik, Iceland

Ante-Rooms and Doffing Rooms

While the UK still requires the design of ante-rooms as part of and negative pressure isolation exam room, many of the states in the US have eliminated this requirement and leave the decision to each design team as to whether or not ante-rooms will be added to a design. It is our belief that the ante-room will be reconsidered as a design priority and defined as a requirement in the next round of planning standards are defined in each state. The EDs that do have ante-rooms (but no doffing rooms) are starting to utilize the corridors outside the rooms as the “donning/dressing” areas, entering a door directly into the exam room, and using the ante-room as the “doffing/undressing” area. This movement from dressing (corridor) into room and then out through the doffing area allows for a one-way flow and limits cross contamination.

When EDs have the opportunity to refurbish or design a new facility, they should consider the placement of isolation rooms along the exterior wall. The sample plan below shows the decontamination/ isolation suite at Adena Health ED in Chillicothe, Ohio, USA. This suite allows access from the central decontamination shower into two separate isolation rooms. The isolation rooms can also be accessed directly from the exterior through the toilet/shower rooms associated with the iso-rooms. Donning alcoves and ante/doffing rooms are also part of the design providing one-way flow out of the room without contaminating the donning area.

Additional items being considered and implemented by clinical staff include the placement IV poles and medication dispensing machines outside the isolation rooms and running the lines back to the patient in the isolation room. This allows nurses to monitor the medications without having to gown in PPE and enter the room. Hands-free communication devises are also being used allowing physicians to communicate with nurses in the isolation room if needed without having to gown/enter the isolation rooms. One client in the US is using baby monitors for this communication, and there are reports of personal radios being used in the UK!

Doffing at Staff Support Spaces

Ante-rooms for donning PPE and doffing rooms for disposing of PPE are being utilized or rapidly developed in many EDs with the influx of virus-related patients. But not many EDs have configured spaces in support of staff decompression areas such as break rooms and locker rooms. Consideration should be given for the reverse flow of having a place for staff to dispose of PPE as the enter a staff-support area and then an area to don the PPE before entering back into the ED.

Separation of Staff?

While great attention is being given to segmenting patients, little attention has been given to segmenting of staff other than splitting people into working in the “COVID19 vs Non-COVID” care zones. Dr. Debra West of Assuta Ashdod Medical Center in Israel explains there “shift change” in the ED as one that keeps separation of “out-going” and “on-coming” staff. She states that “we have gone to a division of organic teams with nursing staff, doctors, administrative staff, etc. We work in 4 teams, 12 hour shifts 07:00-19:00 and 19:00-07:00. The teams do not meet. Handover is done over the phone with the team that is leaving will stay in the ED for verbal handover, the receiving team being staged in the ambulatory ED (which has been closed due to decreased numbers). Immediately after handover one team leaves out the back door, the next team enters through the front door.” This type of “staff flow” adds another level of contamination control and can easily be accommodated in most EDs.

There are examples in England of staff using local hotel sites (since travel and tourism has evaporated) allowing staff to remain local. Staff are using the hotel accommodations as a way to avoid bringing infection home to their families, but we have to ask ourselves about the mental and emotional impacts of such family separations in the long-term.

Isolation Trauma Rooms

Similar to operating theatres, most governing authorities in various locations around the world dictate that ED trauma/resuscitation rooms need to have positive air flow to insure that airborne pathogens do not contaminate the patient or supplies in that room. With the COVID19 crisis, more and more EDs are trying to reconfigure one of their trauma rooms to negative pressure to keep its air inside the room with controlled venting only. Engineering specialist Eric Sherman advises against this temporary change: “Consistent with the guidance from the vast majority of national organizations, converting these existing trauma rooms to negative is not advisable; however, there is a safe alternate practice where a trauma room can be used with the infected patient population. This would include the addition of one or more adjoining vestibules used as airlocks. The environment in the trauma room can be positive with respect to these intermediate rooms and these rooms can be negative with respect to adjoining ED area. This change in room configuration coupled with active pressure controls, monitoring, and staff procedural modifications can allow for the isolation of infectious patients while preserving the directional airflow protecting patients and supplies.”

Many of the newer ED designs that we are developing include multiple trauma rooms with one room being an isolation trauma negative pressure room such as our client at Caboolture Hospital, Caboolture, Queensland, Australia. While designing the room is the easy part, the need to develop protocols (and large ante rooms!) for the multiple care partners and support personnel to access a trauma patient in this room is the challenge to the clinical teams. Additional considerations include the pathway to CT and the potential for contamination as the patient is transported to/from this imaging modality. HMC Westeinde hospital in Den Haag, Netherlands, avoids this challenge by incorporating a portable CT that slides between two resuscitation rooms thus eliminating the need to transport the trauma patient to another CT room.

The days are ending of “open” trauma suites with multiple trauma stretchers lined up with no physical separation of the patients. Major trauma centers, such as Robert Wood Johnson University Medical Center, in New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA, has multiple trauma rooms separated with sliding doors thus allowing the rooms to be linked together while still allowing for a room to be closed off from the others (see photo below).

Site Considerations and Mobile Structures

Most disaster tents have defined set-up locations near the ambulance parking and stretcher entry vestibule into the ED. Most EDs responding to the COVID19 crisis have placed a tent on the walk-in side of the building for exterior screening of patients prior to entering the ED facility. This planning for tents in the front and back of an ED will be commonplace in the future and have design considerations for exterior facility hook-ups for regular power, emergency power, electronical charting, heating, medical gases and plumbing/water supply. The challenges to tent structures are noted by Eric Sherman who states that “temporary facilities such as tents and trailers provide the benefit of physical separation of COVID versus non-COVID patients, but when coupled with the lack of engineering controls, cold climates, and limited medical gas and plumbing infrastructure, create boundaries to the level of safety that can be provided to healthcare providers and acuity of patients processed.”

Segmenting Mechanical/Air Infrastructure Systems

The vast majority of facilities taking action to define separate and air-isolated care zones are finding that their infrastructure systems in terms of air handling and exhaust are not adequate to properly protect healthcare providers and patients from the potential risk of cross contamination. Eric Sherman has assisted clients in managing some of these shortcomings by working with them to install temporary partitions and accompanying mechanical systems inside their existing ED, creating dedicated testing areas adjacent to their ED, and activating clinical areas as interim overflow ED’s. He explains that “compartmentalization of ED areas should be a key consideration provided with infrastructure that can be segregated and protected from cross-contamination. This could include the ability to make compartments of the ED negative, 100% exhaust dedicated to a compartment, and pressure monitored zones. Depending on overall size of the ED, segregated air handling may be considered; however, in smaller units, air handling can be shared with provisions to segregate air returns. This should be coupled with physical access barriers to provide safety, control healthcare provider and patient flow, and allow areas to develop pressure differentials.”

It has been our experience that the planning for separate/segregated air “zones” in the ED is always a part of the early planning process, but tends to get eliminated from consideration due to budget impacts (Sherman estimates a 20% increase in mechanical infrastructure cost to deliver multiple air “zones” in a typical ED). However, with the recent experience of COVID19 on everyone’s minds, the need to segregate mechanical zones in the ED should be a key consideration and priority in the future. Sherman adds that “systems supporting the entire ED should be evaluated from an infrastructure standpoint. Considerations should be made in air handling for redundancy of equipment, ability to process 100% outside air, level of filtering, level of control, ability to increase air changes, evaluation of safeties, humidification, and evaluation of modes of operation. Exhaust systems should also be evaluated for route, redundancy, segregation, and flexibility, and control. The air distribution systems should be considered for support of directional airflow, cascading pressure, and protection of healthcare providers. Supplemental sterilization systems such as UV and electronic filtering systems should be considered to support not only the ED but adjacent patient occupancies. Infrastructure systems should be designed to support a modular concept with flexibility, sizing, and redundancy of not only equipment but also distribution to anticipate what could be dramatic changes in use.”

And while, historically, the consideration to segment air systems into various zones is dismissed due to the budget impacts, recent ED design teams are now reconsidering that decision. Our client in Australia is just wrapping up schematic design and has the following opportunity:

“Regarding COVID –I have raised with Metro North Hospital and Health Service that we need to massively increase the negative pressure capability of the new ED and clinical wing, which they now believe should be considered. The COVID crisis came at the right time for us to experience new flow and better understand the need for pressure-segmenting of various care zones in the future ED.”

Sean Keogh, MD, Service Line Director

Caboolture Emergency, Woodford Correctional Centre and Kilcoy Hospital

Queensland, Australia

Long-Range Design Considerations

In summary, there are many design considerations that can better position our Emergency Departments for future pandemic/epidemic events. These items include:

- Multiple Entry Doors: Whether multiple doors are used daily, such as for separate entries for Adults and Children, or whether usually-alarmed fire exits are able to convert to alternative entry points, we must determine how various patients types may be directed to enter a facility during the next pandemic.

- Interior Screening Locations: We must consider how the “temporary tents” that have screened COVID19 patients in the front of many existing EDs can be used as a template to redesign public ED entry spaces inside our buildings. How do we configure our public areas with appropriate isolation/negative-pressure to allow for rapid distribution and screening of patient types inside the facility BEFORE they access the actual care zones?

- Reception Desks: Greeter desks, reception areas and Pivot Nurse locations will be designed with appropriate plexiglass or bullet-resistant screens to limit human-to-human transmission of future viruses. These design components will be considered in parallel to all security concerns for clinical and reception staff.

- Decontamination Showers: Can the currently underutilized Decontamination Showers be utilized for alternative entries and exits during the next pandemic? Consideration for both ambulance area and walk-in area decontamination facilities must be considered.

- Non-Clinical Areas: Will future project budgets for non-clinical areas such as administrative suites be expanded to include support for immediate implementation of medical gas and other infrastructure systems to allow for immediate conversion to clinical space?

- Immediate Access to Isolation Rooms: Access directly from public areas, and even the exterior of the building, immediately into Isolation Rooms, without passing through the main ED clinical area, must be considered during design.

- Conversion to Isolation Rooms: Will non-clinical, and even regular clinical (non-isolation rooms) be designed to readily accept portable HEPA filters (“plug and play”) and have access to 100% outside air if facilities need to immediately multiply the quantity of isolation rooms in the future?

- Isolation Zones: Mechanical systems must allow us to segment the ED into various negative pressure zones, and potentially allow us to define positive-air care zones for differing contagions. These zones should be accessible from outside entry door and should be considered as you design the type and location of decontamination showers. Multiple zones should be considered beyond just symptomatic and non-symptomatic allow further segregation of patient types.

- Doffing: While ante-rooms have been considered for donning of PPE prior to treatment room entry, the doffing process and securing of contaminated items will be a much higher priority moving forward. Will doffing areas be defined as mandatory spaces in new design guidelines moving forward?

- Internal Results Pending: Social distancing and safe harboring of patients awaiting results will need to be better defined for future Results Pending areas. Since these areas multiply the turnover rates of exam rooms, we can’t allow the pandemic to push us to eliminate these spaces from the usual ED design.

- Entry and Exit Points for Staff: Flow of staff coming on and off shifts should be considered. Entry and exiting of staff support spaces should be designed with donning and doffing support spaces that may be utilized for other support spaces and transitioned for pandemic support if needed.

- Multiple Floors: If an ED is being designed over multiple floors, design teams need to determine the potential use of areas during a future pandemic and work with clinical teams to define the safest pathways throughout the building.

- Trauma Rooms: While 99% of the time the positive-pressure trauma rooms support patient clinical safety, the need for additional positive-pressure treatment areas to support pandemic related trauma cases need to be considered.

With each of these considerations, the biggest struggle will be how to utilize the available budget on “usual” ED design features versus defining portions of the budget that will be applied to pandemic related design components. These discussions and decisions need to be pro-actively completed at the beginning of a project and not added at the end of a design phase “hoping you have extra money” in the budget. Who ever has “extra money” in a budget? Many challenges are in front of us and both design professionals and clinical leaders as we set the course for new EDs during the design process and with the pandemic those challenges have just multiplied.

Summary

Emergency Department personnel are some of the most flexible people we have ever worked with and they tend to readily accept immediate changes in flow, technologies, communications and room-use changes for the betterment of their patients. What is troubling is the many chief complaints that all but evaporated in most EDs… where are the heart-attacks, belly-pains, cancer-symptomatic patients? We believe a wave of sick patients (non-COVID) are lurking out in out communities afraid to come to the ED. For this reason, we believe ED volumes will bounce back once this crisis has stabilized, the question is when will that be?. Public Health England just reported on April 16 that weekly visits for the week of April 6, 2020 were over 70,000 – up from 58,000 the week before but still way down from the 175,000 weekly average from September through March.

ED people are our modern-day super-heroes and we should all work to support them as best we can as we work to define, test and integrate changes in operations and facilities in support of the immediate COVID19 impacts and the long-range planning of the next “super-bug” that is lurking just around the corner.